Cape Town, SOUTH AFRICA – Thirty years after South Africa’s fight for freedom against apartheid, the country has come a long way, but still has work to do.

Listen to the author read an audio recording of this article:

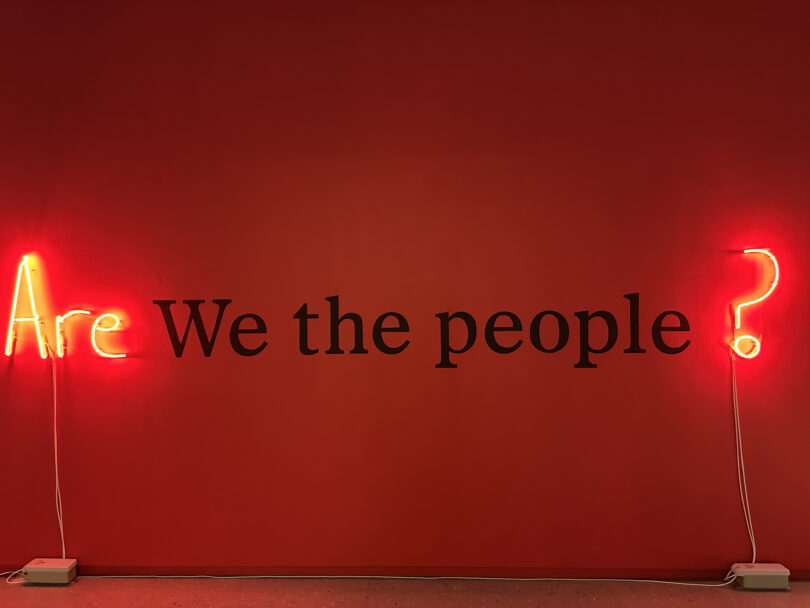

During the 2025 Global Conference in Cape Town, Youth Journalism International students explored this journey at the Norval Foundation. There, the exhibit We, the People: 30 years of Democracy in South Africa showed the work of over 120 artists who explored what democracy means today.

Nelson Mandela became president and South Africa rejoined the Commonwealth in 1994, which makes 2024 the 30th year of democracy in the country.

The Norval Foundation’s exhibition, which closed in November, was guest curated by Liese van der Watt. It is split into four sections: To Belong, To Be Heard, To Protest, To Care.

To Belong

This section asks who belongs to the land and how people find their place in a society still shaped by apartheid. One striking work is the 2024 collaborative piece “Untitled” by Ben Stanwix and Zwelendaba.

The artists use ear tags, the kind used to identify cattle, to create a landscape of abstract markings. The shapes look like a map, but you can’t read it.

It makes you think: does belonging come from ownership, ancestry or something else? The patterns cover the wall, some bright, some faded, forcing you to walk around them and take it in from different angles.

To Be Heard

This section focuses on telling stories that are often ignored. Serge Alain Nitegeka’s 2009 work “Black Subject” uses charcoal and acrylic on wood to show figures trapped in crates and boxes, too big for the space they’re in.

You can almost feel their weight pressing against the edges.

Nitegeka was 11 when he fled Rwanda during the genocide and spent years moving between countries. His work captures the tension of being forced to leave home, carrying only what you can, and trying to fit into a new life.

Jane Alexander’s “Frontier with Ghost” (2007) and “Corporal” (2008) show figures caught in strange, ghostly spaces. They lean, twist, or slump, stuck in the edges of their frame.

You can imagine the stories of people whose voices were silenced, trapped in history.

Orkin’s “PrEP, Present, Post” (2020) uses clay to stack pointed forms that look like tiny towers. The shapes are symbolic of three HIV medicines: before, during, and after exposure.

The clay looks raw and absorbent, as if it could hold or spill liquid at any moment.

To Protest

Protest has always been part of South Africa’s democracy. It gives people a way to speak up and hold leaders accountable. Two of the galleries showed sculptures, videos and other works that captured courage, anger and resistance.

A standout video piece by Lerato Shadi shows a woman in her home village of Lotlhakane in Mahikeng forcing herself to eat red soil while snot runs down her nose.

The video loops endlessly and demands attention. It is shocking and uncomfortable, but it makes you stop and think.

Eating soil was used as a method of suicide by enslaved Africans. Here, it shows the struggle to hold onto ancestral land and resist oppression.

Other protests are also shown. In 2014, University of Cape Town student Chimani Maxwele threw human excrement on the statue of British industrialist Cecil John Rhodes. This act sparked campaigns like #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall.

The exhibition also shows the murder of 14-year-old activist Stompie Seipei. Winnie Mandela, the president’s former wife, was arrested for her role in orchestrating his murder and was convicted of his kidnapping.

These works show that protest can shock, disturb, and force change. But as importantly, it can challenge authority and demand attention.

To Care

This section looks at how people care for each other and the land. Simon Gush’s video Without Light (2016) uses an empty factory and flickering lights to show how work continues even after official hours. The room goes dark and bright again, making you feel their dependence on electricity.

The piece makes you think about how life slows down when power goes out.

Patrick Bongoy’s “Killing Time” (2017) takes industrial waste like rubber, fiber and old tires and weaves them into sculptures. They look almost like giant baskets or twisted plants.

The work makes you notice the mountains of waste created and challenges us to think about reuse and sustainability.

Both pieces emphasize responsibility – for one other, the land, and the resources we all depend on.

Works like Willem Boshoff’s “Ostrakon” (2003), lists 534 names on scarred and burnt ceramic tiles, reflecting on memory, loss, and the fragments of history that democracy seeks to acknowledge but cannot fully access.

Walking through the galleries, it becomes clear that democracy is not just a political achievement but an ongoing project.

From struggles over land to the voices of queer South Africans, from shocking acts of protest to the call to care for one another, the exhibition celebrates what has been achieved but reminds us that the work is far from finished.

For students, the experience was eye-opening. The exhibition encouraged us to confront uncomfortable truths, imagine better futures and celebrate the courage of those who continue to fight for a democratic nation.

Anjola Fashawe is a Senior Correspondent with Youth Journalism International.