Cape Town, SOUTH AFRICA – Yusuf Larney, owner of a Cape Malay restaurant in the Bo Kaap, is an incredible resource for anyone interested in the history of the area.

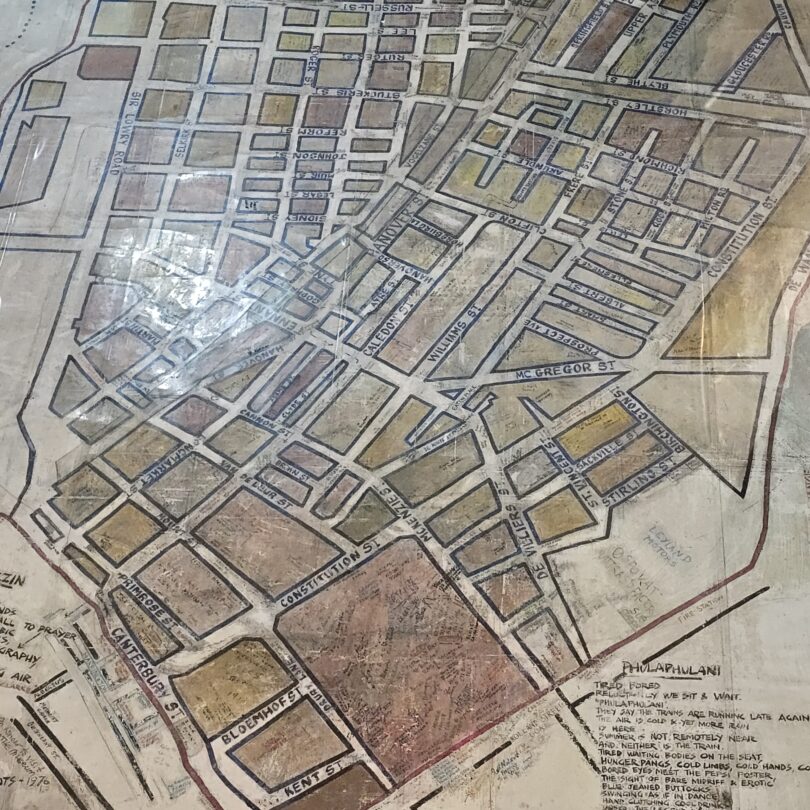

During Youth Journalism International’s Global Conference in Cape Town, Larney told us about the history of a part of Cape Town known as District Six.

Listen to an audio recording of this article:

He spoke about its diversity, saying that the South African author Richard Rive, described District Six as such a special place that it constituted an entirely different continent.

This fascinated me, so when we visited the District Six Museum, I had my eyes open for Rive’s books. In the museum gift shop, I found his book, ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six. It was my favorite purchase from Cape Town.

The book is a partially fictionalized account of life in District 6, particularly the lives of those in a row of houses – despite being far from grand – known as ‘Buckingham Palace.’

Rive himself exists as a character in the book, although a very minor one, and one with clear differences from his real life self.

Robin Malan, a celebrated South African writer, states in the introduction that Rive made himself 10 in 1955 – even though he would have actually been in his 20s. Malan believed that this was a way to separate Rive the author, from Rive the character.

“The writer has chosen to distance himself,” wrote Malan. “to leave centre-stage to the characters.”

The book is divided into three parts – Morning, Afternoon and Night. Each takes place in a different year, 1955, 1960, and 1970, respectively.

Rive’s character is only truly present in the introductions to each part, where he writes a more poetic version of his life in District Six.

“Night, 1970” is naturally both the final and darkest part of the novel. In the first parts, life is mostly happy – though “Afternoon, 1960” brings with it whisperings of apartheid law coming to the district.

Despite the darkening horizon, Rive presents a cast of absurd characters – Zoot, Pretty-Boy, the Butterfly, the Jungle Boys, and many more characters full of life and whimsy.

My favorite names in the book belonged to the two Knight brothers – the younger labelled Last-Knight, and the elder named Knight-Before-Last.

All the characters were witty, constantly having to solve silly problems, and always coming out on top. Pretty-Boy always had a friend willing to sell him things at bargain price – conveniently, the same things that the shopkeeper Mr. Katzen was missing the next day.

The Butterfly was bold, and always ready to defend her home. Zoot accidentally got his house painted completely pink – perils of trusting Pretty-Boy and Oubaas.

White characters were not always the villains – the ones of the District aided their friends and neighbors. The Irishman, Mr. O’Grady, and his odd family added to the novel, as his son Elvis put on shows for the (almost literally) captive audience of Zoot and Pretty-Boy.

They were all hilarious and seemingly undefeatable, but somehow also felt real. I rooted for all of them.

This makes it all the more crushing when reality sets in. Apartheid is coming to the District, and her people cannot win this battle.

“They had taken our past away and left the rubble,” Rive wrote.

Through the story of Mr. Katzen, the Jewish shopkeeper, Rive drew parallels between Apartheid and the Holocaust. Katzen suddenly moved out of his comedic role as the often-fooled shopkeeper, instead transforming into a rebellious figure, refusing to allow the government to buy his property.

Katzen defends and fights for the non-white members of District Six till his death. Speaking of his past in Germany, he said, “They regarded us as untermenschen – sub-human … I cannot forget what they did to us in Germany. So my heart is with all the untermenschen, whoever and wherever they are.”

Still, there was no halting the South African government. In the final scenes of the novel, Zoot is left behind in the wreckage of what was once his home. Everyone has left or been made to leave. He walks alone and a flame flickers in the rubble, desperate to stay alive. But it is too late.

That is the saddest thing about historical fiction – you already know how the story ends, and you cannot change it.

These events did happen. Maybe not to Zoot, the Jungle Boys or the Knights – but they happened to people just like them.

As Malan wrote in his introduction, the book is “about the spirit of the people who lived in it (District Six).”

Rive himself never got to see the end of apartheid, and his book instead serves as a reminder of the past.

Zoot’s last words in the novel stayed with me: “I promise you that our children and the children of those who are doing this to us, will join together and they will see that this will never happen again.”

Anya Farooqui is a Reporter with Youth Journalism International from Pakistan. She wrote this review and made the audio recording.

Holly Hostettler-Davies is an Associate Editor with Youth Journalism International from Wales. She contributed a photo to this article.