Greensboro, North Carolina, U.S.A. – At first glance, the blue and pink lunch stools seem like typical pieces of furniture. Vintage-looking with fraying edges, they appear to be from a throwback movie.

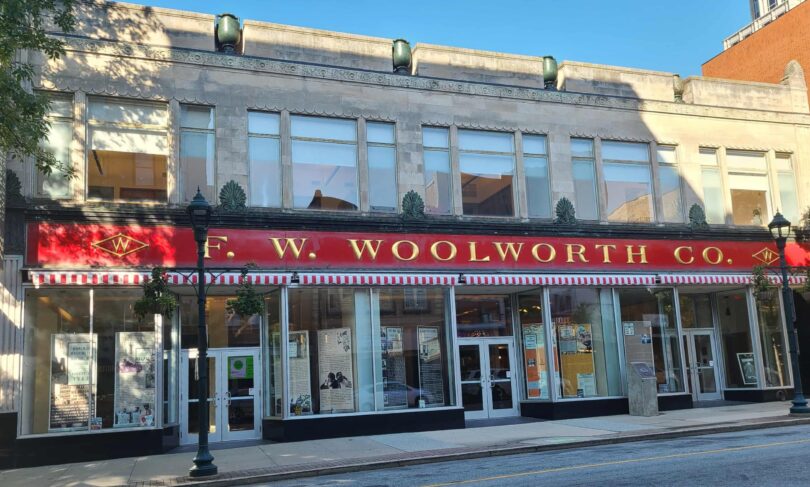

But these lunch counters are originals from the Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina. They became a stage for the 1960s lunch sit-ins, started by four college students on Elm Street in Greensboro.

Listen to a recording of this story:

“They changed America and ignited the Civil Rights movement,” said Darren McGill, a tour guide at the International Civil Rights Center & Museum.

Now, nearly 65 years later, the original Woolworth store is closed, but in its place is the museum, which preserves the site of one of the most influential non-violent protests in the history of the United States.

The museum opened February 1, 2010, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the start of the national student sit-in movement, the day four courageous North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University freshmen, sat down at the whites-only lunch counter and asked to be served.

The A&T Four

The men – widely known as the A&T Four – were David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and Joseph McNeil.

On the nearby A&T campus, a statue depicting the men stands in front of the Dudley Memorial Building.

Inspired by leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and the Freedom Riders, the four freshmen sat on lunch stools in the Woolworth store, demanding service on February 1, 1960.

As in many places, non-whites were prohibited from sitting or being served in establishments. Since the four students were Black, they were denied service at Woolworth countertops.

They remained seated – but not served – until the store closed. All four of them came back the next day with students from neighboring universities, including Bennett College. The students took turns sitting in the ‘white-only’ stools, demanding to be served.

Museum exhibits showed the students were frequently threatened, harassed, and intimidated by white people.

McGill explained that when Woolworth employees refused to serve Black students at its counter, the sit-ins continued, attracting more participation from students across the state. Students at the historically Black Dudley High School in Greensboro joined during the summer, when many university students returned to their home states.

By July 25, 1960, Woolworth – after losing money and customers, and intense media coverage for its discriminatory policies – desegregated its lunch counter.

The Greensboro sit-ins influenced other student nonviolent protests across the nation, according to McGill, including the Children’s March in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Students from historically Black colleges and universities also engaged in sit-ins to advocate for the just treatment of minorities.

Relics from an ugly time

Divided into several exhibitions, the museum memorializes the history and struggle of Black Americans in their fight for freedom and civil rights.

Through its Hall of Shame, the museum makes clear what the Jim Crow South and its racial segregation laws really meant for Black Americans and other people of color. It starts with an art installation of the American flag.

“The United States and its flag are like a quilt,” said McGill. “We are all a complex tapestry, woven together with all of our differences, heritages, and ethnicities.”

But behind the flag, McGill said, is a more sinister picture of slavery and the systematic separation of the people who helped build this country.

With a change in lighting, various Jim Crow era artifacts — ‘WHITES ONLY’ signs, confederate flags and other relics – are visible behind the U.S. flag.

There’s an authentic Ku Klux Klan robe on display, a gift to the museum by family members who were shocked to find the uniform of the white supremacist group among a relative’s possessions.

The Hall of Shame serves as an intense introduction to America’s difficult history of violence, hate, and systemic displacement.

There are disturbing photos of violence and intimidation on display, including a Ku Klux Klan cross burning, and images of victims who were brutally killed or maimed because of their ethnicity or their involvement in the Civil Rights movement.

One photo shows 14-year-old Emmett Till’s mutilated body after racists lynched him in Mississippi in 1955 and dumped his body in a river.

“There were many, many bodies in that river,” McGill said. “Emmett was just another one of them.”

At the time, Till, visiting Mississippi from Chicago, was accused of whistling at a white woman – a charge the woman eventually recanted.

His mother, Mamie Till, held an open-casket funeral for Till, exposing to the masses the vicious beating he endured. The horrible image of the teenager in the casket was seen across the country and opened many eyes to the violence of the American South.

The lunch counter

In the museum, the lunch counter is the centerpiece. The interior remains original and vividly shows the segregation under Jim Crow laws.

Non-white customers “were restricted and rejected just because of the color of their skin,” McGill said, pointing to the lunch counter chairs. “It took the courage of four college students for us to be here today – otherwise, everyone who wasn’t considered white wouldn’t have been allowed to sit here.”

While white customers were allowed to sit and eat, anyone else had to pick up their food to take out.

Today, the International Civil Rights Center & Museum stands as both a memorial and a lesson — a place where history’s injustices meet the ongoing call for equality.

Dorothy Quanteh is a Reporter with Youth Journalism International from Maryland, U.S.A. She reported and wrote this story.

Lina Marie Schulenkorf is a Correspondent with Youth Journalism International from Dresden, Germany. She reported and wrote this story.

Sreehitha Gandluri is a Senior Correspondent with Youth Journalism International from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She contributed to this story and made the audio recording.